Apartheid (“apartness” in the language of Afrikaans) was a system of legislation that upheld segregationist policies against non-white citizens of South Africa. After the National Party gained. The apartheid government used what I would like to call The apartheid segregation plan of education – I want to believe that the decree was used as the government’s first approach to exclude.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apartheid. |

Social apartheid is de facto segregation on the basis of class or economic status, in which an underclass is forced to exist separated from the rest of the population.[1] The word 'apartheid', originally an Afrikaans word meaning 'separation', gained its current meaning during the South African apartheid that took place between 1948 and early 1994, in which the government declared certain regions as being 'for whites only', with the black population forcibly relocated to remote designated areas.

Urban apartheid[edit]

Typically a component in social apartheid, urban apartheid refers to the spatial segregation of minorities to remote areas. In the context of the South African apartheid, this is defined by the reassignation of the four racial groups defined by the Population Registration Act of 1950, into group areas as outlined by the Group Areas Act of 1950.[2] Outside of the South African context, the term has also come to be used to refer to ghettoization of minority populations in cities within particular suburbs or neighbourhoods.

Notable cases[edit]

Latin America[edit]

Brazil and Venezuela[edit]

The term has become common in Latin America in particular in societies where the polarization between rich and poor has become pronounced and has been identified in public policy as a problem that needs to be overcome, such as in Venezuela where the supporters of Hugo Chavez identify social apartheid as a reality which the wealthy try to maintain[3] and Brazil, where the term was coined to describe a situation where wealthy neighbourhoods are protected from the general population by walls, electric barbed wire and private security guards[4] and where inhabitants of the poor slums are subjected to violence.[5]

Europe[edit]

France and Ireland[edit]

The term social apartheid has also been used to explain and describe the ghettoization of Muslim immigrants to Europe in impoverished suburbs and as a cause of rioting and other violence.[6] A notable case is the social situation in the French suburbs, in which largely impoverished Muslim immigrants being concentrated in particular housing projects, and being provided with an inferior standard of infrastructure and social services.[7] The issue of urban apartheid in France was highlighted as such in the aftermath of the 2005 civil unrest in France.[8] It has also be used to describe the segregation in Northern Ireland.

South Africa[edit]

How to download all photos from icloud on mac catalina. In South Africa, the term 'social apartheid' has been used to describe persistent post-apartheid forms of exclusion and de facto segregation which exist based on class but which have a racial component because the poor are almost entirely black Africans.[9][10] 'Social apartheid' has been cited as a factor in the composition of HIV/AIDS in South Africa.[11]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Charles Murray. The advantages of social apartheid. US experience shows Britain what to do with its underclass – get it off the streets. The Sunday Times. April 3, 2005.

- ^South Africa Glossary, impulscentrum.be

- ^Paul-Emile Dupret. Help Venezuela Break Down Social Apartheid. Le Soir. Sep 14, 2004.

- ^Michael Lowy. The Long March of Brazil's Labor Party. Brazil: A Country Marked by Social Apartheid. Logos: A Journal of Modern Society and Culture, vol.2 no.2, Spring 2003

- ^Emilia R. Pfannl. (May 2004). 'The Other War Zone: Poverty and Violence in the Slums of Brazil'. Damocles. Harvard Graduate School of Education. Archived from the original on May 2006.

- ^'Muslim mothers promote diversity at schools in France'. The Express Tribune. 2015-08-13. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- ^Urban apartheid in France, mondediplo.com

- ^Civil Unrest in France, riotsfrance.ssrc.org

- ^Kate Stanley. Call of the conscience; As circumstances focus Western eyes on Africa, American visitors find the place less a mystery than they expected. Star Tribune (Minneapolis, MN), October 1, 2000.

- ^Andrew Kopkind. A reporter's notebook; facing South Africa. The Nation: November 22, 1986.

- ^Rochelle R. Davidson. HIV/AIDS in South Africa: A Rhetorical and Social Apartheid. Villanova University (2004).

Apartheid, the Afrikaans name given by the white-ruled South Africa’s Nationalist Party in 1948 to the country’s harsh, institutionalized system of racial segregation, came to an end in the early 1990s in a series of steps that led to the formation of a democratic government in 1994. Years of violent internal protest, weakening white commitment, international economic and cultural sanctions, economic struggles, and the end of the Cold War brought down white minority rule in Pretoria. U.S. policy toward the regime underwent a gradual but complete transformation that played an important conflicting role in Apartheid’s initial survival and eventual downfall.

Although many of the segregationist policies dated back to the early decades of the twentieth century, it was the election of the Nationalist Party in 1948 that marked the beginning of legalized racism’s harshest features called Apartheid. The Cold War then was in its early stages. U.S. President Harry Truman’s foremost foreign policy goal was to limit Soviet expansion. Fifa 98 soundtracks. Despite supporting a domestic civil rights agenda to further the rights of black people in the United States, the Truman Administration chose not to protest the anti-communist South African government’s system of Apartheid in an effort to maintain an ally against the Soviet Union in southern Africa. This set the stage for successive administrations to quietly support the Apartheid regime as a stalwart ally against the spread of communism.

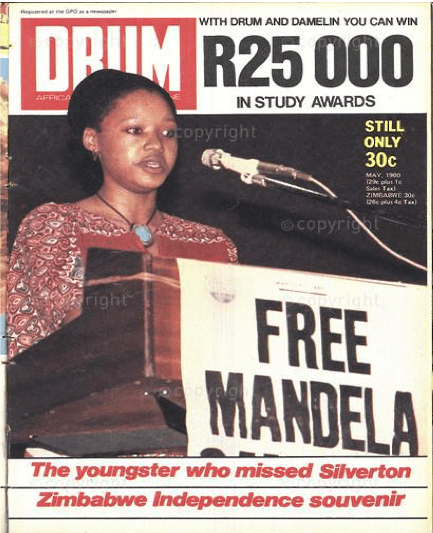

Inside South Africa, riots, boycotts, and protests by black South Africans against white rule had occurred since the inception of independent white rule in 1910. Opposition intensified when the Nationalist Party, assuming power in 1948, effectively blocked all legal and non-violent means of political protest by non-whites. The African National Congress (ANC) and its offshoot, the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), both of which envisioned a vastly different form of government based on majority rule, were outlawed in 1960 and many of its leaders imprisoned. The most famous prisoner was a leader of the ANC, Nelson Mandela, who had become a symbol of the anti-Apartheid struggle. While Mandela and many political prisoners remained incarcerated in South Africa, other anti-Apartheid leaders fled South Africa and set up headquarters in a succession of supportive, independent African countries, including Guinea, Tanzania, Zambia, and neighboring Mozambique where they continued the fight to end Apartheid. It was not until the 1980s, however, that this turmoil effectively cost the South African state significant losses in revenue, security, and international reputation.

The international community had begun to take notice of the brutality of the Apartheid regime after white South African police opened fire on unarmed black protesters in the town of Sharpeville in 1960, killing 69 people and wounding 186 others. The United Nations led the call for sanctions against the South African Government. Fearful of losing friends in Africa as de-colonization transformed the continent, powerful members of the Security Council, including Great Britain, France, and the United States, succeeded in watering down the proposals. However, by the late 1970s, grassroots movements in Europe and the United States succeeded in pressuring their governments into imposing economic and cultural sanctions on Pretoria. After the U.S. Congress passed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act in 1986, many large multinational companies withdrew from South Africa. By the late 1980s, the South African economy was struggling with the effects of the internal and external boycotts as well as the burden of its military commitment in occupying Namibia.

Defenders of the Apartheid regime, both inside and outside South Africa, had promoted it as a bulwark against communism. However, the end of the Cold War rendered this argument obsolete. South Africa had illegally occupied neighboring Namibia at the end of World War II, and since the mid-1970s, Pretoria had used it as a base to fight the communist party in Angola. The United States had even supported the South African Defense Force’s efforts in Angola. In the 1980s, hard-line anti-communists in Washington continued to promote relations with the Apartheid government despite economic sanctions levied by the U.S. Congress. However, the relaxation of Cold War tensions led to negotiations to settle the Cold War conflict in Angola. Pretoria’s economic struggles gave the Apartheid leaders strong incentive to participate. When South Africa reached a multilateral agreement in 1988 to end its occupation of Namibia in return for a Cuban withdrawal from Angola, even the most ardent anti-communists in the United States lost their justification for support of the Apartheid regime.

The effects of the internal unrest and international condemnation led to dramatic changes beginning in 1989. South African Prime Minister P.W. Botha resigned after it became clear that he had lost the faith of the ruling National Party (NP) for his failure to bring order to the country. His successor, F W de Klerk, in a move that surprised observers, announced in his opening address to Parliament in February 1990 that he was lifting the ban on the ANC and other black liberation parties, allowing freedom of the press, and releasing political prisoners. The country waited in anticipation for the release of Nelson Mandela who walked out of prison after 27 years on February 11, 1990.

The impact of Mandela’s release reverberated throughout South Africa and the world. After speaking to throngs of supporters in Cape Town where he pledged to continue the struggle, but advocated peaceful change, Mandela took his message to the international media. He embarked on a world tour culminating in a visit to the United States where he spoke before a joint session of Congress.

Apartheid Worksheets - ESL Printables

After Prime Minister de Klerk agreed to democratic elections for the country, the United States lifted sanctions and increased foreign aid, and many of the U.S. companies who disinvested in the 1980s returned with new investments and joint ventures. In April 1994, Nelson Mandela was elected as South Africa’s first black president.